|

The religious painting

What little has survived of Early Byzantine monumental

painting, comes  mainly

from funerary monuments, such as catacombs, or from churches

in marginal areas where climatic conditions favoured the preservation

of the medium. The former category of monuments shows a variety

of abbreviated religious representations and symbols in a

naturalistic style largely dependent on pagan imagery. The

latter category is best illustrated by the wall paintings

of Bawit and Saqqara in Egypt, which exemplify the rich provincial

style of Coptic art. mainly

from funerary monuments, such as catacombs, or from churches

in marginal areas where climatic conditions favoured the preservation

of the medium. The former category of monuments shows a variety

of abbreviated religious representations and symbols in a

naturalistic style largely dependent on pagan imagery. The

latter category is best illustrated by the wall paintings

of Bawit and Saqqara in Egypt, which exemplify the rich provincial

style of Coptic art.

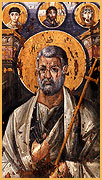

More typical of the Early Byzantine metropolitan style

are the portable icons. These are panels of wood painted in

encaustic, a method in which pigments are mixed with wax.

Icons with portrait busts or standing figures of Christ, the

Virgin and Child, saints, prophets, and archangels, were important

in both public and private worship. Some were credited to

have prophylactic and healing powers, or to have been miraculously

created. The iconoclast reaction of the eighth-ninth centuries

resulted in the  destruction

of a great number of them, but several

pre-iconoclast

examples

have been preserved in the remote monastery of St Catherine

on Mount Sinai, where they were brought by pilgrim visitors

from around the empire or sent as gifts from the capital (the

monastery being an imperial foundation). The Sinai icons of

St Peter and the Virgin enthroned have been attributed to

Constantinople because of their classical conception and high

quality. The former icon shows a naturalistic portrait of

the saint, placed against a niched wall bellow three bust-medallions

representing Christ, the Virgin and St John the Evangelist.

The type may have developed from the pagan Roman custom of

placing portraits in funerary contexts; similar portraits

are known from the burials of Roman colonists at Fayoum, Egypt.

The second icon pictures a solid three-dimentional Virgin

and Child in a similar architectural setting, enthroned between

two saints (possibly Theodore and George) and two angels.

The static frontality of the saints contrasts with the averted

gaze of the Virgin and the Child or the sharp mouvement of

the angels glancing upwards at the hand of God with its band

of light. The type of the enthroned Virgin (or Christ) also

derives from Roman portraiture, particularly from the representations

of the emperor and other dignitaries. destruction

of a great number of them, but several

pre-iconoclast

examples

have been preserved in the remote monastery of St Catherine

on Mount Sinai, where they were brought by pilgrim visitors

from around the empire or sent as gifts from the capital (the

monastery being an imperial foundation). The Sinai icons of

St Peter and the Virgin enthroned have been attributed to

Constantinople because of their classical conception and high

quality. The former icon shows a naturalistic portrait of

the saint, placed against a niched wall bellow three bust-medallions

representing Christ, the Virgin and St John the Evangelist.

The type may have developed from the pagan Roman custom of

placing portraits in funerary contexts; similar portraits

are known from the burials of Roman colonists at Fayoum, Egypt.

The second icon pictures a solid three-dimentional Virgin

and Child in a similar architectural setting, enthroned between

two saints (possibly Theodore and George) and two angels.

The static frontality of the saints contrasts with the averted

gaze of the Virgin and the Child or the sharp mouvement of

the angels glancing upwards at the hand of God with its band

of light. The type of the enthroned Virgin (or Christ) also

derives from Roman portraiture, particularly from the representations

of the emperor and other dignitaries.

|